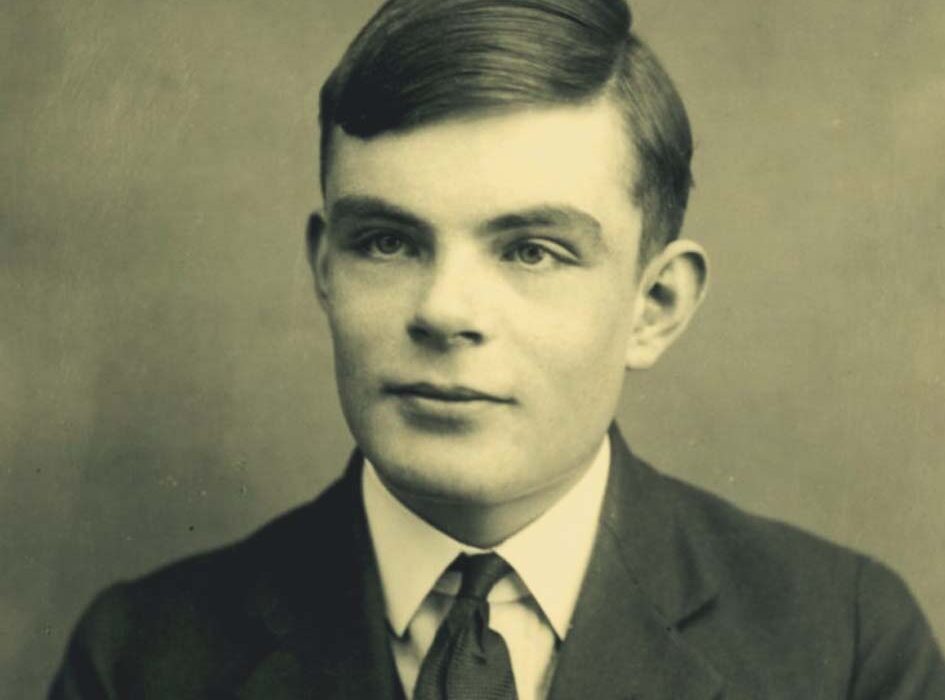

To save and be betrayed by your own country – the life of a World War II hero and the father of computer science.

Alan Turing was born on the 23rd of June 1912 in London. Son of a civil servant with ties to the historic aristocracy, Turing had the privilege of attending a top private school and quickly excelled in his academics – particularly in the field of mathematics. After finishing high school, he was gifted a scholarship to study maths at the University of Cambridge. Even in such a competitive environment surrounded by some of brightest minds in the UK, Turing’s incredible logic skills, dedication, and ability to think outside of the box, made him easily stand out of the crowd. In 1934, he was elected to join a fellowship at Kings College for his research in probability theory – A branch of mathematics focussed on the analysis of random possibilities. During his time as a fellow, he would go on to publish several well recognised papers that touched upon new topics such as computer programming and artificial intelligence.

Turing’s work as a Nazi code breaker would begin in the summer of 1938 as he joined the Government code and cypher school. Not long after the second world war broke out however, he would be moved to work at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire. Known by his peers as an excentric figure who could often be seen wearing a gas mask to prevent hay fever, Turing would choose to take on the so-called impossible task of breaking the German Enigma while there. The Enigma was a machine consisting of cogs that could be configured in many ways in order to encrypt secret messages, for example if you wrote the letter “A” the machine would light up and decrypt it to “K”. It was known that the machine had up to 150 quintillion different possible settings which would be changed at exactly midnight every day, giving the Allied forces only 24 hours to try to extract Nazi information from these secret messages – a time consuming and virtually impossible feat. As previously mentioned though, Alan was highly dedicated and able to come up with abstract ideas to solve problems, therefore he determined that the only way to break the enigma would be with another machine.

Alongside a team of mathematicians, linguists and even crossword enjoyers including Marian Rejewski who had worked on a simpler version of the enigma in Poland – Turing began to work on his decoding machine titled “The Bombe.” It worked via passing through an infinitely long piece of paper with 1s and 0s which had been translated from the morse code of the encrypted German messages. The Bombe had many enigma dials which would compare the intercepted message with commonly used phrases such as the weather and “Heil Hitler” to work out the settings of the encryption device and decrypt the message.

Over the course of the war, the Germans had tried to starve Britian by destroying food ships crossing the channel with U-Boats. This had proved a major problem solved only be severe rationing, however now with the decryption machine working miracles, the allied forces knew exactly where the U-Boats were positioned at all times allowing the food ships to take different routes and avoid detection. Although, with this working so well, there were concerns that the Nazis would realise that the enigma had been broken and build an entirely different encryption device. Therefore, to combat this suspicion, the allies had to come up with clever excuses such as flying spotter planes over the U-Boats to “coincidently” locate their position despite it already being well known by military officials. The enigma code was kept a secret for nearly thirty years following the end of the war.

After Britian’s wartime victory, Turing went back to his studies in mathematics and computer science contributing to many of the first computers and their programming languages. He also theorised and promoted the idea of artificial intelligence, describing the human brain as a “trainable, universal machine” – the reason we now have the “Turing test” to determine whether a user is a real person or just a computer. Although despite his great work, it was soon about to grind to a halt as Turing was arrested for his homosexuality in 1952. A fact that he hadn’t kept particularly secret but was confirmed by police after a supposed break into Turing’s house in which nothing had been stolen. In court he was given two choices, either to go to prison or receive hormonal treatment, wishing to continue his research he chose the second however this treatment would significantly alter him both physically and mentally. On the 7th of June 1954, aged only 41, Alan was shockingly found dead in his home from cyanide poisoning. Though it is suspected that his death was a result of suicide, this has never been officially confirmed and may have been accidental.

Turing’s treatment from the government he once worked with so closely has long been a topic of outrage. It took until 2009 for the Prime Minister at the time Gordon Brown to publicly apologise and until 2013 for him to be granted a royal pardon from Queen Elizabeth II. Though Turing’s life ended in tragedy, his work has been continued for decades after his death with great leaps and bounds being made in computer science, from quantum technology and artificial intelligence to gaming and cyber security.